Usain Bolt is the fastest human, but a cheetah can outrun him by nearly three times his top speed. Nature is powerful and its brilliance is inspiring designers to create performance-enhancing technology and Sidelines is diving into the details.

Image by Mony Hemetsberger from Pixabay

For athletes, practicing sport relies on a seamless partnership with nature. Sailors work with the breeze to fill their sails, swimmers dance with a steady flow of water and climbers shift their movements with the patterns of a cliff face.

Athletes train relentlessly to be the best, fine-tuning their diet, exercise and technique to reach peak performance. While their efforts are celebrated, it’s nature’s animals that have truly perfected the art of movement.

This is why designers have turned to biomimicry – the process of learning from nature to design materials – to enhance athlete performance.

Now they design sails inspired by dragonfly wings that improve speed, swimsuits that mimic the buoyancy of sharkskin and climbing shoes that offer gecko-like grip.

These new innovations have performed in the biggest arenas, broken world records and won gold medals but left sport governing bodies wrestling with what has gone too far.

Can the natural inspired enhancements become too unnatural and give athletes an ‘unfair’ advantage?

The natural world is powerful and its intricate blueprints are helping designers transform the way athletes train, compete and win.

No one understands this better than Simon De Myttenaere, Co-founder and COO of Bioxegy.

“We believe that nature is the most advanced engineer and lab on earth,” he says.

De Myttenaere leads a team of biologists and engineers using nature as inspiration to create technological solutions and enhancements.

He says, “I was on my sofa and just scrolling on Facebook at the time and I saw a video of a French speaker talking about biomimicry but not really doing anything about it. I discovered the concept and spoke about it to one of my close friends. We realised that it could be interesting to launch a design office to answer the needs and build technology inspired by nature’s knowhow.”

“With the equipment we now make for athletes, we give them the possibility of becoming much better than their ancestors’.”

De Myttenaere and his team are currently working on a new ski design.

He says: ”We were inspired by ‘sandwich structures’ and layers that you can find in shells. We also worked on the texture of the ski for a better slide and were inspired by the scales of animals – and this really helped us improve.”

De Myttenaere is not the only one to gain inspiration from nature. One of the most notable displays of biomimicry in sport was in the 2008 summer Olympics in Beijing.

That year Michael Phelps won eight gold medals and set seven world records, all while wearing a Speedo LZR Racer suit.

The swimsuit, designed by Fiona Fairhurst, mimicked the efficiency of sharkskin.

The jet-black swimwear, accented with silver seams, was designed to reduce drag and enhance buoyancy. It compressed the muscles and reduced vibrations to improve the swimmer’s performance.

Jonathan Yates, Senior Publicity Director at Speedo says, ”The Speedo LZR Racer was a game-changer in competitive swimming.”

The swimsuit was successful, but caused controversy.

De Myttenaere says, “I think the swimming technology is indeed efficient and very useful but in a certain way it does completely change human capacities and abilities.”

That year the suit made waves. It was worn by countless other athletes and Speedo reported that 98 percent of medals were won by swimmers wearing the LZR suit.

Former Olympics press officer Taylor Mooney wrote: “We saw a huge difference in times after the introduction of the more lightweight, skin-like swimsuits.”

The suit was so successful that media organisations swarmed, calling it ‘technological doping,’ and the international swimming federation banned it.

Mooney wrote: “This was largely down to concerns over fairness and the integrity of the sport.

“In 2009, new regulations were introduced which have remained in place to this day. Along with material allowances during competitions, there are also restrictions on the coverage these suits can have on an athlete. Men’s suits are allowed only from waist to knees and women’s suits are allowed from shoulders to knees.”

World Aquatics rule SW 10.9 now states that ‘No swimmer shall be permitted to use or wear any device or swimsuit that may aid his/her speed, buoyancy or endurance during a competition.’

Athletes, coaches and sport scientists are increasingly looking for technology that will maximise potential and push them towards victory.

Tara Magdalinski, Pro Vice-Chancellor at Swinburne University of Technology, says: “There has always been some urge to find some sort of winning formula, whether it’s some special herb you find out in a field or whether it’s through the application of scientific, physiological or biological principles to enhance athletic performance.”

Magdalinski has completed extensive research into sport studies, particularly exploring the relationship between performance technology, nature and the athletic body.

“Obviously in many sports there has to be a physiological edge because it’s just the athlete and their performance. Whereas in something like cycling, motor racing, skiing, there is technology that you can use, enhance and improve.

“I think the British cycling team is a great example because they train under the cloak of darkness and they cover up their new bikes so that no one can see their latest thing that’s coming to the Olympics.”

In one of her books, Magdalinski explores the question, ‘What is the nature of athletic performance?’ to understand the fine line between ‘unnatural’ enhancements and essential adaptations in sport.

To do this, she highlighted another famous example of biomimicry in sport: the cheetah-inspired running blade, designed by amputee and inventor Van Philips.

He replicated the way cheetahs’ hind legs store and release energy with each stride. The curved spring blade stores the runner’s energy as they step down, then releases it in a powerful motion to propel them forward.

Philips’ flex-foot blade design, with some variation by Icelandic manufacturers Össur, is now used by approximately 90% of Paralympic runners.

Magdalinski says: “Athletes with missing limbs can rely on ‘running blades’ while swimmers can replace missing hands with fins. These are all considered an acceptable alternative for the real thing as opposed to an extension of the body.”

The sharkskin swimsuits and some padded trainers, on the other hand, are considered to be an unfair advantage.

Magdalinski says: “There’s some sort of line, which I think is quite unofficial that we draw, but some of the nature inspired technology is deemed too unnatural.”

As technology advances even prosthetics could push athletes beyond their expected physical capabilities, so should we look at using nature in a different way?

De Myttenaere says: “I think that regarding sports the most important thing today is not to maximise performance but rather secure the athletes during practice. We could make more resistant helmets, gloves etc. that can resist some impacts.

“Spider silk is five times stronger than steel yet it’s incredibly light and flexible. It’s nature’s kevlar and the dream for sports engineering.”

At Bioexgy, De Myttenaere’s team is exploring advancements in protective gear inspired by spider’s silk.

“What’s fascinating is not just the strength, but the energy dissipation and capacity of these fibers. When there’s a sudden impact like a fall from a bike or rugby tackle, it can be absorbed more effectively to reduce harm,” he says.

“Nature isn’t just strong, it’s smart about how it handles stress and it’s a very nice inspiration.”

De Myttenaere is also working on making some skis lighter, as traditional models tend to be quite heavy, making the sport more difficult and less accessible to a wider audience.

“We actually realised while working on sports equipment that it doesn’t just have to benefit the athlete, we could also help the general public in their everyday practice and activities,” he says.

With nature as their guide, De Myttenaere and his team are working on creating a future where sport becomes safer and more accessible.

From elite competition to everyday use, nature’s influence on sports is undeniable. Whether it’s restoring lost ability, enhancing performance, or making it safer and more inclusive, nature is a powerful source of inspiration.

But with nature’s power comes controversy. Questions about whether biomimicry should enhance athletic performance or only create opportunities will remain, but even if designers stop looking at the natural world for inspiration, the bond between athlete and nature will remain.

The connection will exist in the way a rower sways with a flowing river, the way surfers trust the waves to hold them steady and equestrians dance with their horse to one rhythm.

Sidelines Recommends

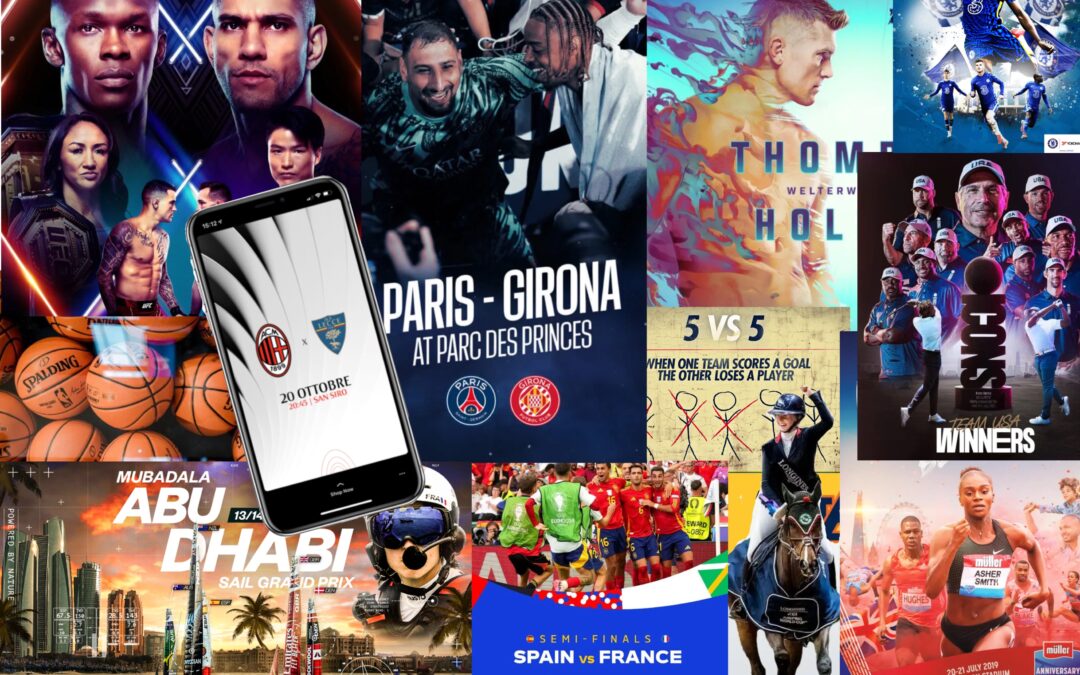

How sports brands stay #Winning

When the noise online matters just as much as the noise in the stands, how do you break through? Sidelines speaks to the sports marketing experts trusted by Red Bull, PSG, and UFC to manage their brand. Like it or not, in a world where everyone’s smartphones are an…

Creating in chaos: the man behind the graphics at Sky Sports

Sky Sports is one of the UK’s breaking sports news powerhouses – but it’s not just the pundits on screen who make it happen. Each transfer and tribute needs visuals carefully curated, which is where Liam Harrison comes in. Graphic designer feels a small word for what…

The virtual advantage: how VR is revolutionising sports training

How is virtual reality influencing the way athletes train and level up their game? Sidelines dives into the future of sports training.