Attached by a 10cm cord, how do visually impaired runners and their guides stay in sync and reach the finish line? With record-breaking athletes, Sidelines brings you an exclusive insight into guide running.

In the Paralympic and sporting world, few partnerships are as vital as that between a blind athlete and their guide runner. Often overlooked, guides are the glue that makes it all happen.

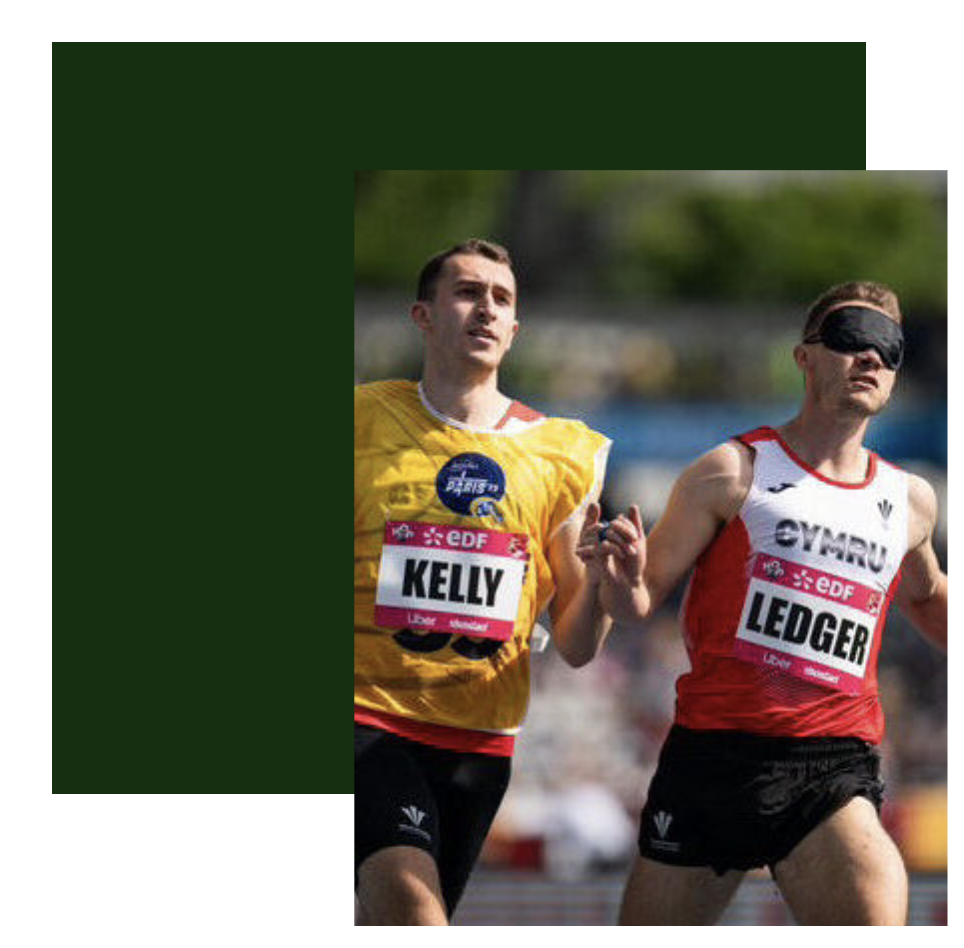

Trust is vital, and for Great Britain and Wales’ leading T11* sprinter, James Ledger, and his guide Greg Kelly, this is no different.

“We are both the athlete in my eyes. Without Greg, I can’t do what I do,” says Ledger.

In their first year as a team, Ledger and Kelly broke the T11 British record for 100 metres, crossing the line in 11.55 seconds.

“We knew it was quick; we could just feel it. When you’re waiting for the clock to come down to see what the time was, seeing ‘British record’ is just an unbelievable feeling,” Kelly says.

“I’m running as fast as I possibly can in the dark,” Ledger says. “I’ve got to trust Greg with everything, and that belief in him lets me fly to my full potential; that is how we beat that record.”

Despite Kelly having never guided a run in his life, their friendship formed quickly, and that translated to results on the track.

“When Greg and I first met, we became bloody good friends,” Ledger says. “That makes everything easier. We understand each other a lot more.”

But what goes into finding a guide fast enough to sprint next to a world-class blind sprinter, but selfless enough to cross the line second?

It was an Instagram ad, put out by Ledger and his coach Matt Elias, which attracted the attention of sprinter Greg Kelly, 25, from Scotland.

“I don’t think guide running would have been on my radar,” Kelly says. “But after seeing the ad and having one conversation with James I saw what his ambitions were to go to the Paralympics and compete abroad, I was desperate to get going.”

Kelly, growing up, was always a sports lover and was focused on football, but when individual medals and national titles for Scotland in athletics (200 metres and 400 metres) started flowing in, he pursued athletics wholeheartedly.

Following a move to Loughborough to study at the University, he progressed his individual athletics career in 200 and 400 metre races, pushing for the 2022 Commonwealth Games in Birmingham.

Whilst that didn’t pan out, timing led him straight into Ledger’s path.

“When I applied to be James’ guide runner – I didn’t train for it,” Kelly admitted. “I actually studied a few YouTube videos and listened to feedback from James following our training sessions.”

Kelly’s lack of experience as a guide runner has never been a stumbling block, as for Ledger, what mattered most was learning the timing, rhythm and understanding of each other and building their relationship.

Guide running is where a sighted guide assists a visually impaired runner, ensuring safety and direction. The guide and runner are tethered by a 10cm cord and communicate constantly to navigate the track together.

And with Ledger having already worked with a guide runner, running at both the 2018 Commonwealth Games in Australia and the 2022 Birmingham Games, he is now an expert.

Ledger, 31, was born in Swansea with bilateral coloboma and nystagmus, a condition affecting his sight and eye movement, leaving him with around 3% total vision.

“From a very young age, my parents quickly realised that the world wasn’t necessarily a visually-impaired-friendly place,” he says.

He discovered running after a discussion with his parents and realised that sitting on the bench for a non-disability football team wasn’t fulfilling a desire for sporting success.

Ledger said: “Dad, I want to be fast.”

It quickly progressed for the young runner, and after joining the Swansea Harriers running team, he was identified as a T12 athlete – which is for athletes with a moderate visual impairment, who have the option to run with or without a guide depending on their level of vision and personal preference. As his sight declined, he transitioned to T11, for runners with a near-total visual impairment. Some can make out an object at 25cm, but all compete with a sighted guide runner in blacked-out glasses.

“One of the things I didn’t realise with becoming a T11 athlete was how hard it was to find a guide,” Ledger says. “I needed a guide who could run 100 metres in 10.5 seconds but it isn’t just about running – they have to guide me, communicate and run within themselves.”

However, the 100 metre sprint is only one aspect of working as a guide runner; at events, there is a lot that goes into getting them across that finish line.

Navigating the venue, making sure they have a safe place to warm up, taking Ledger through the warm up and to the start line, are all important factors which are often forgotten by onlookers.

And then comes the race, where communication and cues are key.

“I’ve got a load of technical cues which I shout throughout the race,” Kelly says. “On top of guide running, it is almost like a coaching role.”

“Sometimes my cues are ‘drive’ or ‘be patient’, but I normally shout numbers like 50 so Ledger knows we are halfway through and should be in his ‘upright phase’ and not driving.”

As they approach the final 10 metres, Kelly will shout “10” and “dip”, preparing Ledger to get ready to lean down, but Kelly has to do the opposite.

“When Ledger leans forward, I have to lean back to make sure he beats me over the line otherwise we would be disqualified.

The result? “I’ve never beaten James in a race,” Kelly laughs, “ He always holds that over me.”

Training when you’re a pair of record holders poses another difficulty. With Kelly in Manchester and Ledger in Cardiff, most of their training is done separately.

“Obviously, in a dream world, I would be on the tether with James everyday, but it doesn’t quite work like that because of location – we make do,” Kelly says.

“We will do an extended period of time monthly, and next month we are going warm weather training, which is our most crucial part to make all the gains whilst working together on the tether.”

It is within these extended periods of training that Kelly can put aside his job for a commercial real estate company and master the art of guide running whilst keeping a clear head in a stressful environment.

This is key because of Ledger’s’ sheer speed.

Kelly says: “James is so sharp out of the blocks that I have to be flat out just to keep up with him, beyond that I’m a bit more relaxed and I can start communicating.

“Sometimes when I’ve guided, it takes me a period of time to think about how I normally run and how I would be able to run any faster than this myself.”

Life in their first year running together hasn’t all been smooth, however.

A severe hamstring tear for Ledger halfway through 2024, during the middle of a race, would bring their 2024 Paralympic aspirations to a standstill.

“To communicate that with Greg, who was still running flat out, was extremely tough,” Ledger says. “It’s definitely the biggest hurdle we have faced so far.”

Kelly adds, “It was around 80 metres where it happened, I thought maybe James had come out of shape, so I pulled the tether and carried on running, but I turned my head and saw him in pain.”

Despite jogging over the line, their time was one they’d have been proud of earlier in the season. They now profess to be faster than ever and have the 2028 Paralympics in sight.

Highs and lows in this profession are common, and whilst this injury hampered their season, success is something Kelly has become accustomed to.

He says, “It is so different succeeding as a guide runner to individually, and it’s probably better.

“We got the British record again last year, that moment when you’re waiting for the clock to come down to see what time it was, because we knew it was fast, is just an amazing feeling to share.”

For Ledger, sharing the success is something which comes as second nature, yet recognition for guide runners hasn’t always come easily. Medals were only awarded to them starting from 2012.

“There are a lot of people who do what I do around the world, who have their guide turn up at a track, go on the tether, run and then wave goodbye. I’ve never been like that.

“If we aren’t right off the track, we aren’t going to be right on the track,” Ledger says.

Continued exposure for the guide running role is something which Kelly always wants to push as it benefits all parties, giving him opportunities he may not have been exposed to.

“I know everyone around me, whether it be friends, family, my club back home, and the company I work for, are all really proud of me for this, and it’s made me individually a better runner,” Kelly says.

And for Ledger, his drive and ambition with the support of guide runners, have allowed him to hit heights he never thought he could.

“As a 14-year-old boy sat on the bench of a non-disability football team, I never would’ve believed I could achieve these things.

Ledger adds, “Guide runners are certainly the unsung heroes of our sport.”

But thanks to athletes like Ledger, they’re becoming increasingly seen.